UEFI vulnerabilities are “the next frontier” in attack vectors, as boot firmware can be persistent on any given target, and runtime services will persist even after an operating system is loaded. And in this new era of very powerful generative pre-trained transformers (GPTs), AI analysis tools are emerging to detect and mitigate such vulnerabilities as never before. In this article, I explore the use of these tools on Tianocore EDKII UEFI builds.

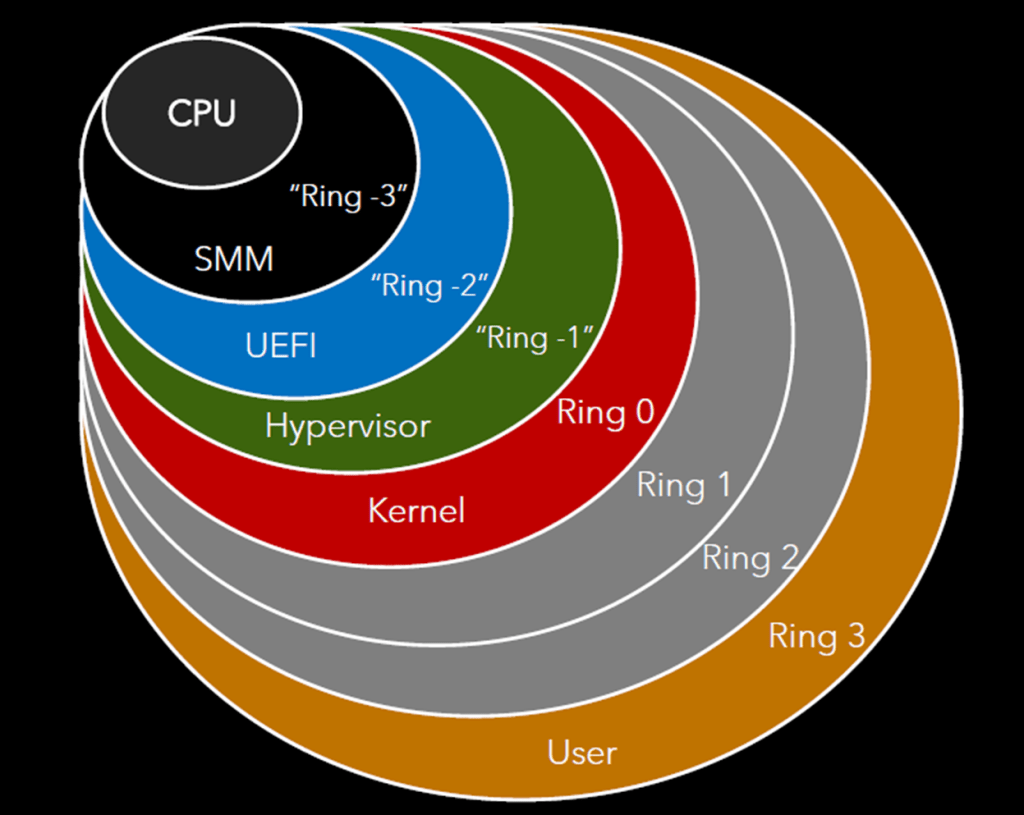

Over time, malware and threats have “gone down the stack”, as privileges increase the closer you get to the silicon. This can be depicted visually by the following:

Caption: Diagram courtesy of Pavel Yosifovich, Windows Internals course

The closer you get to the hardware and silicon (CPU), the more dangerous any vulnerability or threat will be; offset by the fact that attacks at these levels are very difficult to craft. As an example, for silicon, vulnerabilities or trojans could in theory be present, but extremely low-level knowledge, physical access and/or access to the semiconductor fab supply chain would be necessary to take advantage of them.

But firmware, and in this particular instance UEFI, makes for an interesting case study. The UEFI supply chain is relatively fragile; for Intel CPUs, the major suppliers (AMI, Insyde, Phoenix) base their code on the Tianocore EDKII open-source distribution, which in isolation is somewhat flawed; some notebook/server/embedded system OEMs/ODMs make (sometimes random) changes to the base to add their own features; and distribution of security updates is haphazard. Companies like Binarly and Eclypsium do a brisk business in hardening enterprise firmware supply chains.

Given that, I’ve done some research to explore the following:

- How accurate are today’s LLMs at identifying vulnerabilities in UEFI?

- Can correct migitations be crafted to these weaknesses, and easily integrated into an IFWI (Integrated Firmware Image)?

- Are there advantages/benefits to using larger open-source language models (in terms of parameters and tokens) as opposed to off-the-shelf closed-source offerings like ChatGPT, Gemini, etc.?

And I’ll present the findings in a form that others can follow along if interested.

So, with that, let’s proceed.

OVERALL APPROACH

In terms of an overall approach, I wanted to start with an established baseline: a known UEFI build, with source and symbols, and with known vulnerabilities. This is difficult, as most commercial products have their firmware locked down, resident in flash memory, and accessible only as binaries. Fortunately, for the purpose of this study, a publicly available board that meets my criteria does exist: the AAEON UP Xtreme Whiskey Lake board:

Caption: AAEON UP Xtreme Whiskey Lake board

In terms of analysis tools, I plan to compare and contrast the results from:

ChatGPT 5.1

Gemini 3.0

My DGX Spark with model llama3.1:70b

My NVIDIA DGX Spark with model deepseek-r1

But first, let’s compare and contrast older code with known defects to a “golden” baseline of modern firmware: in this case, the CryptoPkg part of the UEFI build. We’ll build an older version of the code that uses OpenSSL 1.1.1j (with known defects); and then compare it against the current version, that incorporates OpenSSL 3.5.1.

BUILDING THE UEFI DEBUG IMAGE WITH SOURCE/SYMBOLS

The UP Xtreme board has a documented, working implementation of what’s termed “MinPlatform” for it within the Tianocore framework. That is, a fully working, mostly open-source, build tree that is available online for anyone to download and play with. I say “mostly” open source because it uses the Intel Firmware Support Package (FSP), and there are binary blobs therein. But that’s OK: the blogs are mostly for silicon initialization, and a small part of the overall build files.

Intel (mostly Harry Hsiung and Laurie Jalstrom, to the best of my knowledge; and my apologies in advance for anyone I neglected to mention) did a terrific job of providing step-by-step instructions on building a bootable UEFI image on this target, based on an older release. The general instructions on how to build the UEFI image are in text form here:

A PowerPoint/PDF with some more detail on building the image is here:

You can see within the GitHub Intel/tianocore-training repository a ton of tutorial material on UEFI; it’s well worth spending some time here learning, if you have technical interest.

You’ll want to obtain a copy of Visual Studio 2019 as well as Git Bash on your local Windows PC build machine.

On that build machine, launch Git Bash and type in the following, essentially downloading with tag edk2-stable202108:

$ cd c:

$ mkdir fw

$ cd fw

$ mkdir UpX

$ cd UpX

$ git clone https://github.com/tianocore/edk2.git

$ cd edk2

$ git checkout 7b4a99be8a39c12d3a7fc4b8db9f0eab4ac688d5

$ git submodule update --init

$ cd ..

Then download edk2-platforms with the August 2021 tag:

$ git clone https://github.com/tianocore/edk2-platforms.git

$ cd edk2-platforms

$ git checkout 40609743565da879078e6f91da76fc58a35ecaf7

$ cd ..

Finally download the edk2-non-osi and FSP repositories:

$ git clone https://github.com/tianocore/edk2-non-osi.git

$ git clone https://github.com/Intel/FSP.git

At this point, the UpX directory should have four subdirectories: edk2, edk2-non-osi, edk2-platforms, and FSP. You’ll also want to download the ASL compiler and NASM assembler to complete the build. They can be obtained here:

Now, it’s time for the build. Launch the Developer Command Prompt for VS 2019 from a CMD line, and change to the Min Platform Build directory:

$ cd c:\Fw\UpX\edk2-platforms\Platform\Intel

You’ll need to do this build with Python 3.8 (sic) on your PC. Once this is installed and set up, fire off the build:

$ python build_bios.py -p UpXtreme -t VS2019

And, voila, in a few minutes, you’ll have all that you need. The complete 2021 release folder is 2.91GB in size, and holds 48,883 files, with 6,812 folders. In zipped form, it is 1.45GB.

Note that in the folder:

c:\fw\UpX\Build\WhiskeyLakeOpenBoardPkg\UpXtreme\DEBUG_VS2019\FV

is the 6,848kB UPXTREME.fd file. We’ll refer to this file in a follow-up article in the series; it is the binary file that we’ll be flashing onto the AAEON UP Xtreme target.

You’ll have noted that we built this with the 2021 stable release commit hash for WhiskeyLakeOpenBoardPackage. This boots on the AAEON UP Xtreme board – at least, it boots on mine. This might change in the future if the AAEON hardware board changes in any way incompatibly with this build.

For the purpose of this study, we’ll also need to do a build with today’s most stable release commit hash. This can be done by repeating the commands above, but this time just omit the two lines:

$ git checkout 7b4a99be8a39c12d3a7fc4b8db9f0eab4ac688d5

$ git checkout 40609743565da879078e6f91da76fc58a35ecaf7

As an FYI: you’ll note that the current most recent stable tag at the time of this writing is edk2-stable202511 (released on November 21, 2025); and its commit hash is 46548b1adac82211d8d11da12dd914f41e7aa775.

Note: The 2021 image, once flashed onto the AAEON Up Xtreme board, will boot; but the 2025 version will not. Apparently, Intel did not do the open-source work to enable this image to boot on this target in follow-up releases; that is left as an exercise for the student. Which brings me to a future interesting project: can AI help us “modernize” UEFI and also tune it to boot upon a specific board topology (essentially, a board support package) in an arbitrary release? What information does it need to succeed at a task like this? This would make for a great learning experience to check out.

ANALYZING THE CRYPTOPKG VIA CHATGPT 5.1

Now, I happen to know that the 2021 build files implement an older, flawed version of OpenSSL: release 1.1.1j. You can verify this by looking in:

C:\fw\UpX\edk2\CryptoPkg\Library\OpensslLib\openssl\include\openssl\opensslv.h

where you’ll see:

#define OPENSSL_VERSION_TEXT “OpenSSL 1.1.1j 16 Feb2021”

OpenSSL makes for an interesting attack surface, as it provides core cryptographic services within UEFI firmware for:

- Secure Boot

- Firmware Image Authentication

- Secure Communications

Note: Some may ask, is this version susceptible to the “Heartbleed” attack that was in the news 10 years ago? The answer is no: Heartbleed took advantage of a buffer overrun bug that was patched in OpenSSL 1.0.1g in 2014 – how time flies!

But, back to the present: let’s feed the old image information into ChatGPT 5.1, and see what it finds.

But first, you need to take into account the limitations of the public GPTs. In particular, here’s what ChatGPT says about that topic, when I once tried to upload an 8GB Intel Processor Trace file to it:

ChatGPT file uploads have a hard per-file cap of 512 MB and text/doc uploads are limited to ~2 million tokens per file (far smaller than your 8 GB trace). The blocking issue is the per-file 512 MB and 2M-token caps, which apply broadly—not just Plus. Pro/Enterprise mainly increase file count/quota, not the single-file size/token limit.

My current context window is about 128k tokens (roughly 400–500 pages of text). That’s the maximum amount of text I can keep “in working memory” at once when analyzing a file or conversation.

ChatGPT will choke on our 2021 and 2025 trees:

The 2021 folder is 2.91GB in size, and holds 48,883 files, with 6,812 folders. In zipped form, it is 1.45GB.

The 2025 folder is 3.58GB in size, holds 43,800 files, with 8,521 folders. In zipped form, it is 2.07GB.

Because of the sizes, neither one of these complete builds, even when zipped, can currently be consumed by ChatGPT. As you’ll see later, this is the essence of my research project: to overcome the limitations of file size and LLM token context windows by using my NVIDIA DGX Spark with open source LLMs and technology. More to come on this topic in follow-up episodes in this series!

But for now, we’ll just focus on the EDKII CryptoPkg module, that contains our flawed OpenSSL implementation in the 2021 tree. The 2021 CryptoPkg folder is 60.2 MB with 18,440 files and 228 folders, and zipped it is 19.6MB. The 2025 CryptoPkg folder is 192MB with 7,242 files, and zipped it is 63.5MB. And we’ll use AI to compare the two and scan for vulnerabilities, knowing that we have an incomplete picture; we’ll need the Spark to dig deeper, later!

The precise prompt I used with the 2021 zipped CryptoPkg file was:

Assume that you are a senior systems engineer with specific expertise in UEFI development and programming. You are attempting to make a UEFI firmware build more secure, and you suspect that the EDK2 CryptoPkg may have some vulnerabilities in it. Could you please scan the attached zip file of the CryptoPkg folder and report on any vulnerabilities you detect?

ChatGPT gave me quite a bit of useful information. It thought for 6 minutes and 41 seconds, and provided the following (abridged substantially):

6. Summary

From the snapshot you provided:

- Definite concern:

- You are bundling OpenSSL 1.1.1j, which is now old; later 1.1.1 releases and OpenSSL 3.x contain additional security fixes. OpenSSL

- Configuration-dependent cryptographic weaknesses:

- MD5 and SHA-1 APIs are compiled in and available to BaseCryptLib consumers because of the ENABLE_MD5_DEPRECATED_INTERFACES and lack of DISABLE_SHA1_DEPRECATED_INTERFACES in CryptoPkg.dsc.

- The Crypto protocol driver tries to block deprecated algorithms, but any module calling BaseCryptLib directly can still use them unless you tighten your build and your PCDs.

- No obvious new buffer-overflow-style bugs in the CryptoPkg-specific wrappers and drivers were apparent from this grep-level scan, and the port uses EDK2’s bounded string helpers for many CRT calls.

If you’d like, next step we can do is: you tell me how you’re integrating this CryptoPkg into your platform (which DSC/FDF, which services you actually use), and I can help you design a hardened configuration (PCDs, build flags, and a checklist to ensure no MD5/SHA-1/TDES/RC4 leaks into the “real” firmware paths).

It’s fascinating to read this analysis. Although no obvious vulnerabilities exist in this build, the fact that MD5 and SHA-1 APIs are exposed, and therefore might potentially be used or taken advantage of, is of concern. And the fact that the UEFI supply chain is so hodgepodge makes this an even more delicate situation.

I next completed the 2025 build, and fed this CryptoPkg.zip into ChatGPT, with this prompt:

Analyze the new CryptoPkg2.zip. Have all the vulnerabilities that you identified in the original CryptoPkg.zip been resolved in CryptoPkg2.zip? If so, please identify them. Also, please separately identify any new vulnerabilities that have been introduced within CryptoPkg2 versus CryptoPkg.

And for completeness, I’ll include the full response, ChatGPT this time taking 3 minutes and 0 seconds to respond:

Short answer:

- No, not all of the originally-flagged issues are resolved.

- The big one (old OpenSSL 1.1.1j) is fixed and the MD5-by-default problem is also fixed.

- SHA-1 is still compiled in and available, so the “config-dependent SHA-1 footgun” remains.

- I don’t see any new obvious vulnerabilities introduced at the CryptoPkg layer by CryptoPkg2, but of course OpenSSL 3.5.1 will have its own CVE profile.

Below is what I actually found in CryptoPkg2.zip.

1. Status of the issues we identified previously

1.1 Out-of-date OpenSSL 1.1.1j

Original problem:

The previous package bundled OpenSSL 1.1.1j, which is now considered legacy in the 1.1.1 line and missing a lot of later fixes.

CryptoPkg2 status:✅ Fixed (and more than you asked for)

In CryptoPkg2.zip:

// CryptoPkg/Library/OpensslLib/OpensslGen/include/openssl/opensslv.h

# define OPENSSL_VERSION_MAJOR 3

# define OPENSSL_VERSION_MINOR 5

# define OPENSSL_VERSION_PATCH 1

# define OPENSSL_VERSION_TEXT “OpenSSL 3.5.1 1 Jul 2025”

So:

- You’re no longer on 1.1.1j at all; this is OpenSSL 3.5.1, not 1.1.1w.

- From the narrow perspective of “old 1.1.1j w/ known issues vs current 3.x”, this is a clear improvement.

Whether 3.5.1 itself is fully up-to-date vs the latest 3.x is a separate (CVE-level) question, but relative to the original vulnerability I flagged, this is resolved.

1.2 MD5 and SHA-1 deprecated interfaces

Previously I called out:

- MD5: enabled by default due to ENABLE_MD5_DEPRECATED_INTERFACES flags in CryptoPkg.dsc → all BaseCryptLib consumers got MD5 APIs compiled in.

- SHA-1: compiled in by default unless DISABLE_SHA1_DEPRECATED_INTERFACES is set; and PcdHashApiLibPolicy could be configured badly.

Let’s see what changed.

1.2.1 MD5

In CryptoPkg/Include/Library/BaseCryptLib.h, MD5 is still gated like this:

#ifdef ENABLE_MD5_DEPRECATED_INTERFACES

// Md5GetContextSize, Md5Init, Md5Update, Md5Final, Md5HashAll …

#endif

But in the new CryptoPkg/CryptoPkg.dsc:

[BuildOptions]

*_*_*_CC_FLAGS = -D DISABLE_NEW_DEPRECATED_INTERFACES

and there are no lines that define ENABLE_MD5_DEPRECATED_INTERFACES anymore (I searched the whole CryptoPkg).

So:

- In CryptoPkg2, MD5 deprecated interfaces are not enabled by default.

- That means Md5* APIs are not compiled at all unless some platform DSC or build config explicitly adds -DENABLE_MD5_DEPRECATED_INTERFACES.

Relative to the original package:

- The “MD5 is globally and silently available” weakness is fixed at the CryptoPkg level.

- If your platform DSC doesn’t re-introduce that define, then MD5 is gone from BaseCryptLib’s public surface.

✅ This previously identified weakness is resolved (with the caveat that you could re-break it yourself in platform build options).

1.2.2 SHA-1

SHA-1 in BaseCryptLib.h is still controlled by:

#ifndef DISABLE_SHA1_DEPRECATED_INTERFACES

// Sha1GetContextSize, Sha1Init, Sha1Update, Sha1Final, Sha1HashAll, HmacSha1*, etc.

#endif

And CryptoPkg2’s CryptoPkg.dsc still does not define DISABLE_SHA1_DEPRECATED_INTERFACES anywhere.

So:

- SHA-1 APIs are still compiled in and available to BaseCryptLib consumers by default.

- If any of your modules call Sha1* or HmacSha1* directly (or misconfigure PcdHashApiLibPolicy), you can still end up using SHA-1 in security-relevant flows.

On the plus side, in CryptoPkg.dec the default hash policy remains:

gEfiCryptoPkgTokenSpaceGuid.PcdHashApiLibPolicy|0x00000002|UINT32|0x00000001

Where, per the comments in that file:

- 0x00000002 == HASH_ALG_SHA256

So the default HashApiLib policy is SHA-256, not SHA-1. That was already reasonably good, and is still true.

But the core issue I flagged originally — that SHA-1 is compiled by default and easy to use if platform code calls into it — is not changed.

❌ SHA-1 availability is still a configuration-dependent weakness.

1.2.3 Crypto protocol driver behavior

CryptoPkg/Driver/Crypto.c still has the same “hard deprecation” wrappers for MD5/SHA-1/TDES/AES-ECB via BaseCryptLibServiceDeprecated():

UINTN

EFIAPI

DeprecatedCryptoServiceMd5GetContextSize (

VOID

)

{

return BaseCryptLibServiceDeprecated (“Md5GetContextSize”), 0;

}

and similar for SHA-1. So:

- Via the EDK II Crypto Protocol/PPI, MD5/SHA-1 remain blocked and will assert/log if used.

- The risk is still via direct BaseCryptLib usage, not via the protocol, exactly as before.

1.3 Risk of accidentally shipping OpenSSL “apps” or test code

The structure remains the same:

- OpenSSL vendor tree: CryptoPkg/Library/OpensslLib/openssl/…

- CryptoPkg unit tests: CryptoPkg/Test/…

CryptoPkg2 still only includes the expected production libraries and drivers in its own DSC/INF files; the “apps” and tests are not referenced for firmware builds.

So nothing here has regressed or improved in a material way. It remains a platform-integration responsibility to ensure you don’t add test modules/openssl apps to your FDF/DSC by accident.

2. New vulnerabilities introduced in CryptoPkg2 vs CryptoPkg?

Within the CryptoPkg layer (not counting OpenSSL’s own CVEs):

- I don’t see any new weak algorithms being enabled by default.

- The MD5 situation improved (no more ENABLE_MD5_DEPRECATED_INTERFACES in the package DSC).

- SHA-1 behavior and the deprecated-service stubs in Crypto.c are essentially the same as before.

I did a quick sweep of EDK-side C sources in CryptoPkg (excluding the raw OpenSSL tree) for classic C disasters (strcpy, strcat, sprintf, gets, scanf, etc.) and didn’t see new direct uses. EDK2 still relies on its own safe CRT shims for most of that.

So from a CryptoPkg-code point of view:

- I don’t see any obvious new vulnerabilities introduced by your update.

- The attack surface has arguably shrunk: old 1.1.1j is gone, MD5 isn’t compiled by default.

The only “new” element that could bring new issues is:

- You’ve moved to OpenSSL 3.5.1, which will have its own vulnerability profile. Compared to 1.1.1j, it will fix a ton of old issues but may have its own newly discovered ones. That’s a net win, but you should still track OpenSSL 3.x advisories and keep up with point releases.

Without external CVE data and a full diff against the old OpenSSL tree, I can’t honestly claim zero new vulnerabilities; I can just say nothing in the EDK2 wrapper layer jumps out as a newly introduced problem.

3. Summary by your questions

Have all the vulnerabilities that you identified in the original CryptoPkg.zip been resolved in CryptoPkg2.zip? If so, please identify them.

- Outdated OpenSSL 1.1.1j → ✅ Resolved

- Now using OpenSSL 3.5.1 (opensslv.h in OpensslGen), which eliminates the original “you’re stuck on an old 1.1.1 point release” issue.

- MD5 deprecated APIs enabled by default via package CC_FLAGS → ✅ Resolved at CryptoPkg level

- ENABLE_MD5_DEPRECATED_INTERFACES no longer appears in CryptoPkg.dsc, so Md5* functions won’t be compiled unless your platform explicitly defines that macro.

- SHA-1 APIs compiled by default and available to BaseCryptLib callers → ❌ Still present

- DISABLE_SHA1_DEPRECATED_INTERFACES is still not defined in CryptoPkg.dsc.

- Sha1* and HmacSha1* remain available to any module that includes BaseCryptLib.h.

Also, please separately identify any new vulnerabilities that have been introduced within CryptoPkg2 versus CryptoPkg.

- At the CryptoPkg wrapper/driver level, I do not see any clear new vulnerabilities:

- No new weak algorithms exposed by default.

- Deprecated MD5 handling actually improved (no longer compiled by default).

- Crypto protocol still blocks MD5/SHA-1/TDES/AES-ECB when accessed via the protocol.

- The only significant change is the move to OpenSSL 3.5.1:

- This removes the “stuck on a legacy 1.1.1j” problem.

- OpenSSL 3.5.1 will still have its own CVEs; they’re just likely fewer / more manageable than for 1.1.1j.

If you’d like, next step I’d suggest is:

- In your platform DSC/FDF:

- Add -DDISABLE_SHA1_DEPRECATED_INTERFACES to CC_FLAGS for production builds.

- Grep your platform code for Sha1 / HmacSha1 and confirm you’re not using them in security-critical paths.

If you send me your platform DSC/FDF snippets, I can give you a concrete “hardening patch” to fully close the SHA-1 hole as well.

If you read the analysis carefully, it becomes obvious (as it may have been from the beginning): in large codebases, it’s impossible to fully assess vulnerabilities without looking at the big picture: in this case, analyzing the complete codebase, including the build environment. The above is far from a complete vulnerability analysis. And an additional combination of full static analysis, fuzzing, and dynamic analysis would certainly help.

In my next article in this series, I’ll be using the NVIDIA DGX Spark to perform a more massively comprehensive analysis of the entire codebase – in this case, the entire build tree, which is gigabytes in size.

Caption: NVIDIA DGX Spark, Founders Edition

As a brief introduction, I’ll describe the overall approach, for those who want to run ahead:

Install Open WebUI with Ollama to chat with the model and provide access to RAG.

Use the largest public models that the Spark can comfortably accommodate; in this case:

llama3.1:70b-instruct-q5-K_M

deepseek-r1:70b

Use a high-performance embedding model for RAG: nomic-embed-text.

Pull out of the build tree the necessary and useful files for the analysis: .c, .h, .dec, .inf, etc.

Concatenate all the needed files into one big .txt file.

Split the massive resultant file into smaller chunks, say 20MB in size, so we don’t timeout on the uploads.

Configure the embedding model, and create a Knowledge Base for this application.

If everything goes according to plan, this should be amazing. See you in the next article!